Extreme Weather Events Are Not Increasing: Separating Fact from Fiction

Contrary to widely publicized claims, there is no robust evidence linking global warming to an increase in the frequency or intensity of extreme weather events. While climate models and public discourse often predict worsening hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires, and heat waves, observational data and historical records tell a different story. Natural variability emerges as a more significant driver of these events than human-induced CO₂ emissions.

Hurricanes and Tornadoes

Hurricane Activity Trends

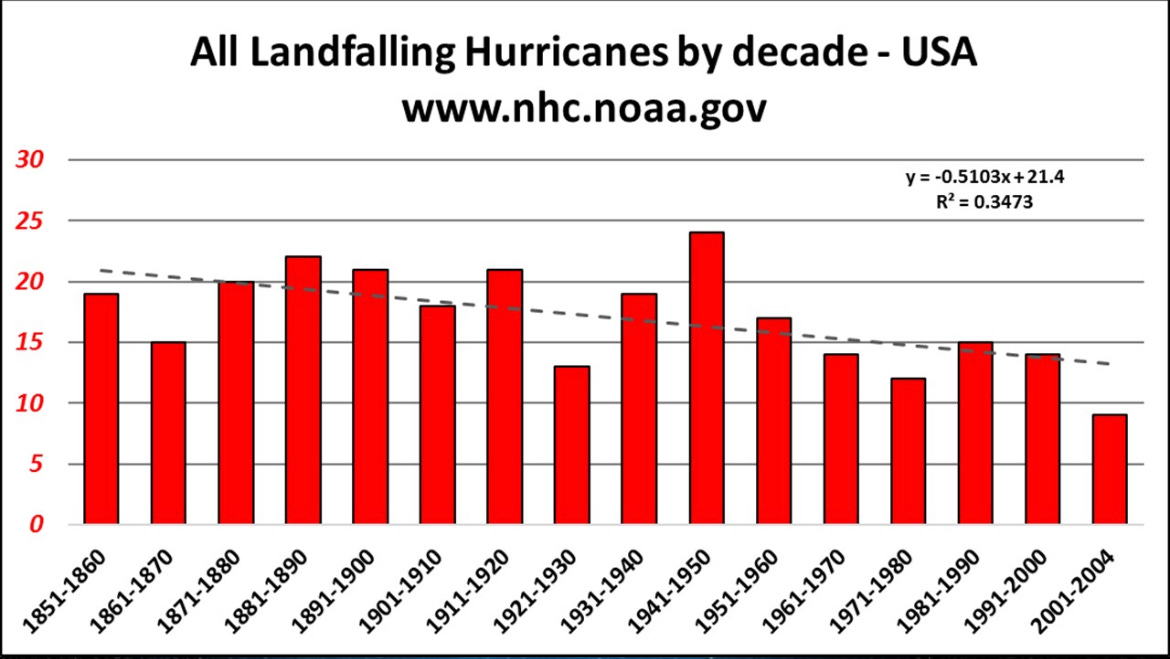

No Significant Increase: According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), there has been no statistically significant increase in the frequency or intensity of hurricanes over the past century.

Historical Variability: The Atlantic Basin Hurricane Database (HURDAT) reveals greater variability in hurricane activity during earlier periods, such as the late 19th and early 20th centuries, than in recent decades.

Category 4 and 5 Hurricanes: The strongest hurricanes do not show consistent trends of increasing occurrence, despite predictions that warmer ocean temperatures would intensify storms.

Tornado Activity Trends

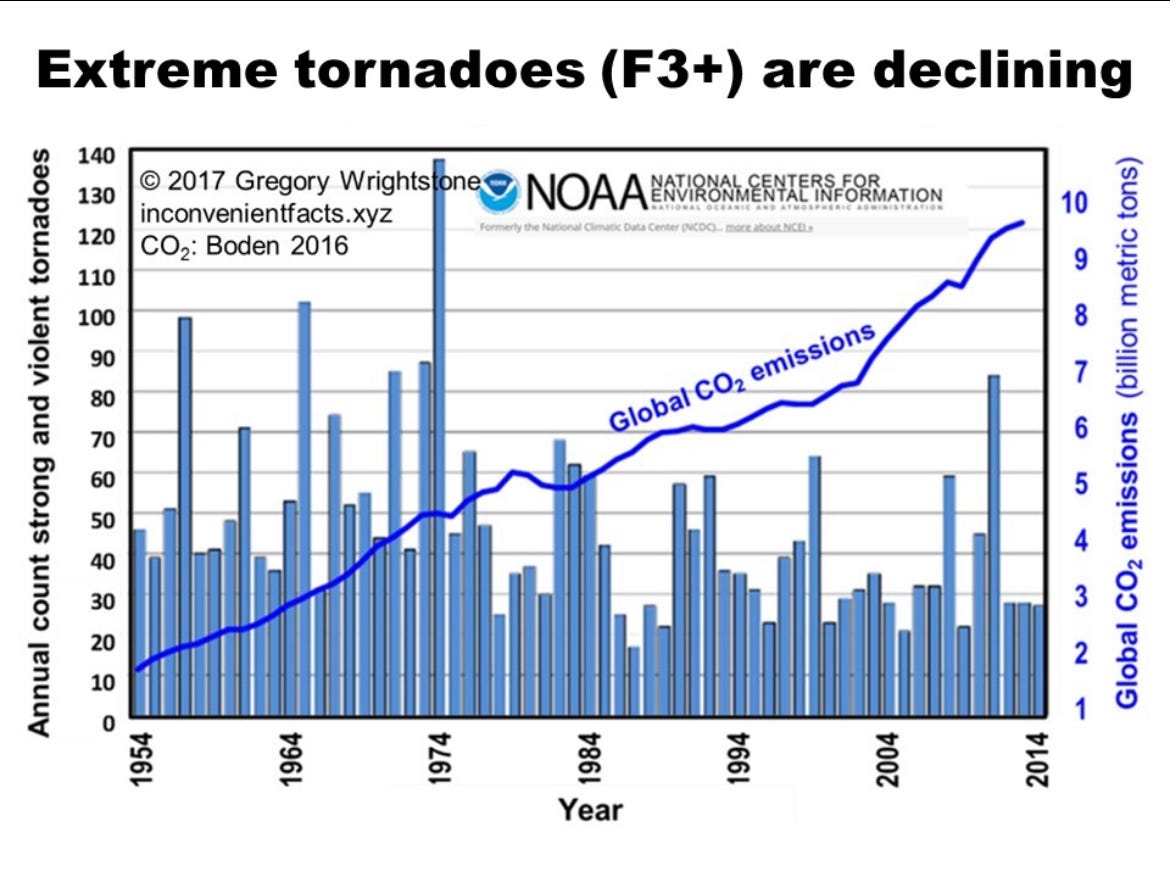

No Upward Trend: NOAA data indicate no clear increase in tornado frequency or strength in the United States, which experiences the highest number of tornadoes globally.

Historical Outbreaks: Some of the most destructive tornado outbreaks occurred before significant industrial CO₂ emissions, underscoring the role of natural variability in tornado patterns.

Forest Fires and Heat Waves

Forest Fire Trends

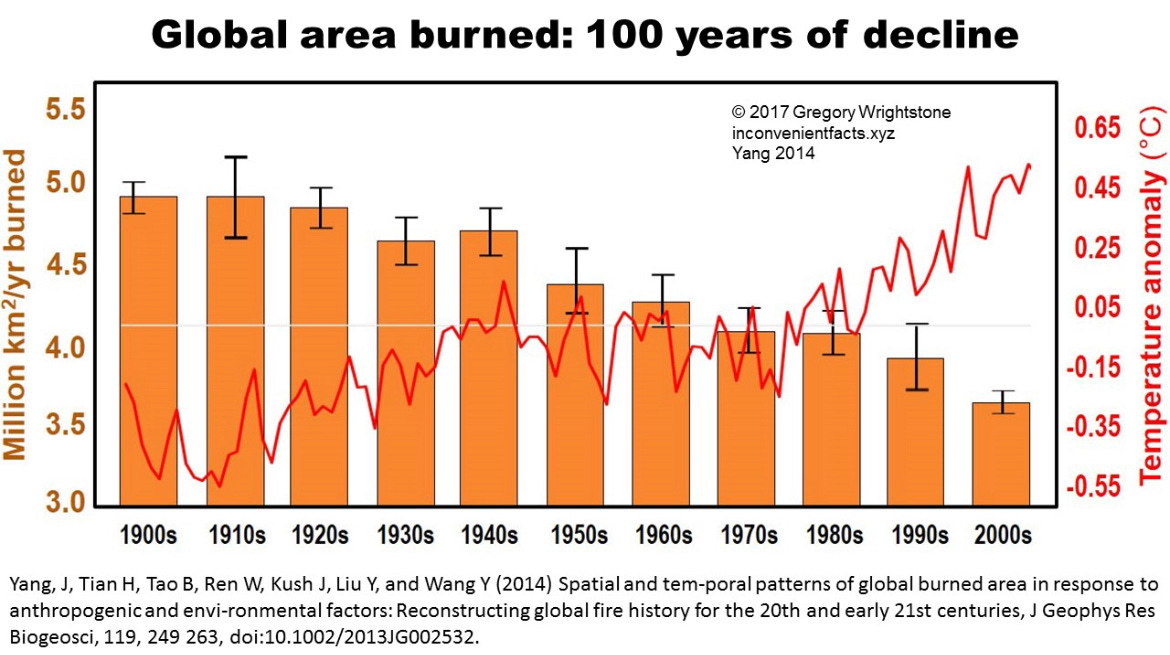

Declining Wildfire Activity: Studies, including those by Flannigan et al. (1998), report declining trends in global wildfire activity over the past century.

Improved Management: Advances in forest management, such as controlled burns and fire suppression techniques, have significantly reduced wildfire acreage in regions like North America and Europe.

Satellite Data: Observations from satellites confirm that the total area burned by wildfires has decreased globally in recent decades, even as media coverage of fire events has surged.

Heat Wave Trends

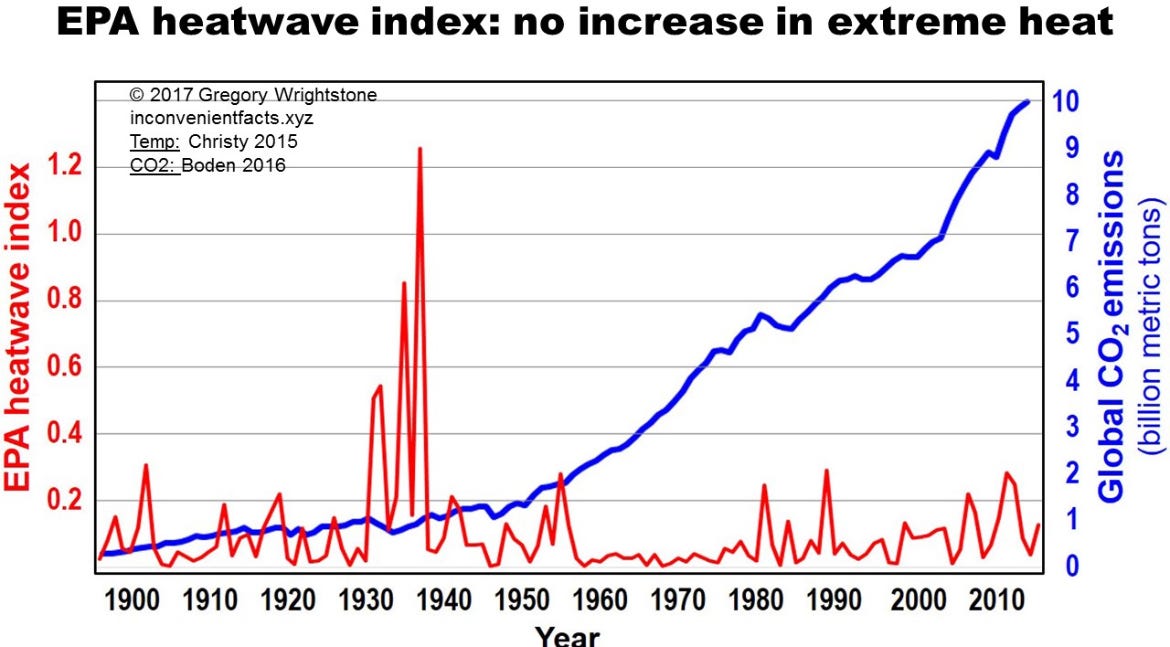

Historical Extremes: The 1930s Dust Bowl Era remains one of the hottest periods in recorded history, with widespread heat waves surpassing those of recent decades.

1936 Heat Wave: The summer of 1936 holds the record as the warmest on record for the contiguous United States, with numerous all-time high-temperature records still unbroken.

Natural Drivers: These extreme heat events were primarily influenced by natural variability, such as ocean-atmosphere interactions, rather than CO₂ levels.

Recent Trends: Declines in heat wave frequency across the Northern Hemisphere challenge projections of more frequent extreme heat due to global warming.

Floods and Droughts

Flooding Trends

No Global Increase: Research shows no consistent increase in global flood occurrences. Localized flooding is often driven by land use changes, urbanization, and deforestation rather than shifts in global climate.

Drought Trends

Regional Variability: Drought patterns vary significantly by region, with no evidence of a global trend toward more severe or widespread droughts.

Rainfall Recovery: Some regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa, have seen increased rainfall in recent decades, contributing to a reversal of desertification trends.

Natural Variability and Historical Context

Historical Weather Extremes

Historical records provide clear evidence of severe weather events long before industrialization:

The Dust Bowl (1930s): This North American disaster was driven by natural climate variability and exacerbated by poor land management.

The Great Hurricane (1780): One of the deadliest hurricanes on record occurred well before significant human CO₂ emissions.

The Role of ENSO

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), consisting of El Niño and La Niña phases, drives significant global weather variability, influencing droughts, floods, and storm activity. These natural cycles often overshadow the impacts of long-term warming trends.

Policy Implications

Adaptation Over Mitigation

Instead of focusing narrowly on CO₂ reduction, policies should prioritize adaptive strategies to protect communities from extreme weather impacts:

Flood Defenses: Invest in levees, stormwater management, and improved drainage systems.

Wildfire Prevention: Expand controlled burn programs, enhance forest management, and allocate resources for firefighting.

Heat Mitigation: Promote urban planning initiatives, such as increasing green spaces and planting trees, to reduce urban heat island effects.

Invest in Research and Preparedness

Enhance disaster response systems, early warning networks, and research on natural variability.

Improve predictive models for short-term phenomena like ENSO to better anticipate extreme weather events.

Acknowledge Natural Variability

Recognize that natural cycles, such as ocean-atmosphere interactions and solar variability, are dominant forces shaping weather patterns. Policies should account for these factors rather than attributing all extreme weather to human-induced CO₂ emissions.

Conclusion

The narrative that global warming is causing more frequent or severe extreme weather events is not supported by empirical evidence. Observational data and historical records highlight the role of natural variability as the primary driver of hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires, and heat waves. By focusing on adaptation strategies and acknowledging natural climate drivers, policymakers can better protect communities from extreme weather while avoiding costly and ineffective CO₂-centric mitigation policies.

References

NOAA. (2022). Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions. Available at: NOAA Hurricane Research

Flannigan, M. D., et al. (1998). Future wildfire in circumboreal forests in relation to global warming. Journal of Vegetation Science, 9(4), 469–476.

Pielke Jr., R. A. (2014). The Rightful Place of Science: Disasters and Climate Change. Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes.

Trenberth, K. E. (1997). The definition of El Niño. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 78(12), 2771–2777.

National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). (2020). Total Wildland Fires and Acres (1960–2020). Available at: NIFC Fire Statistics

Zhu, Z., et al. (2016). Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nature Climate Change, 6(8), 791–795.